LITTLE PIM BLOG

Infographic: The Benefits of Early Language Learning

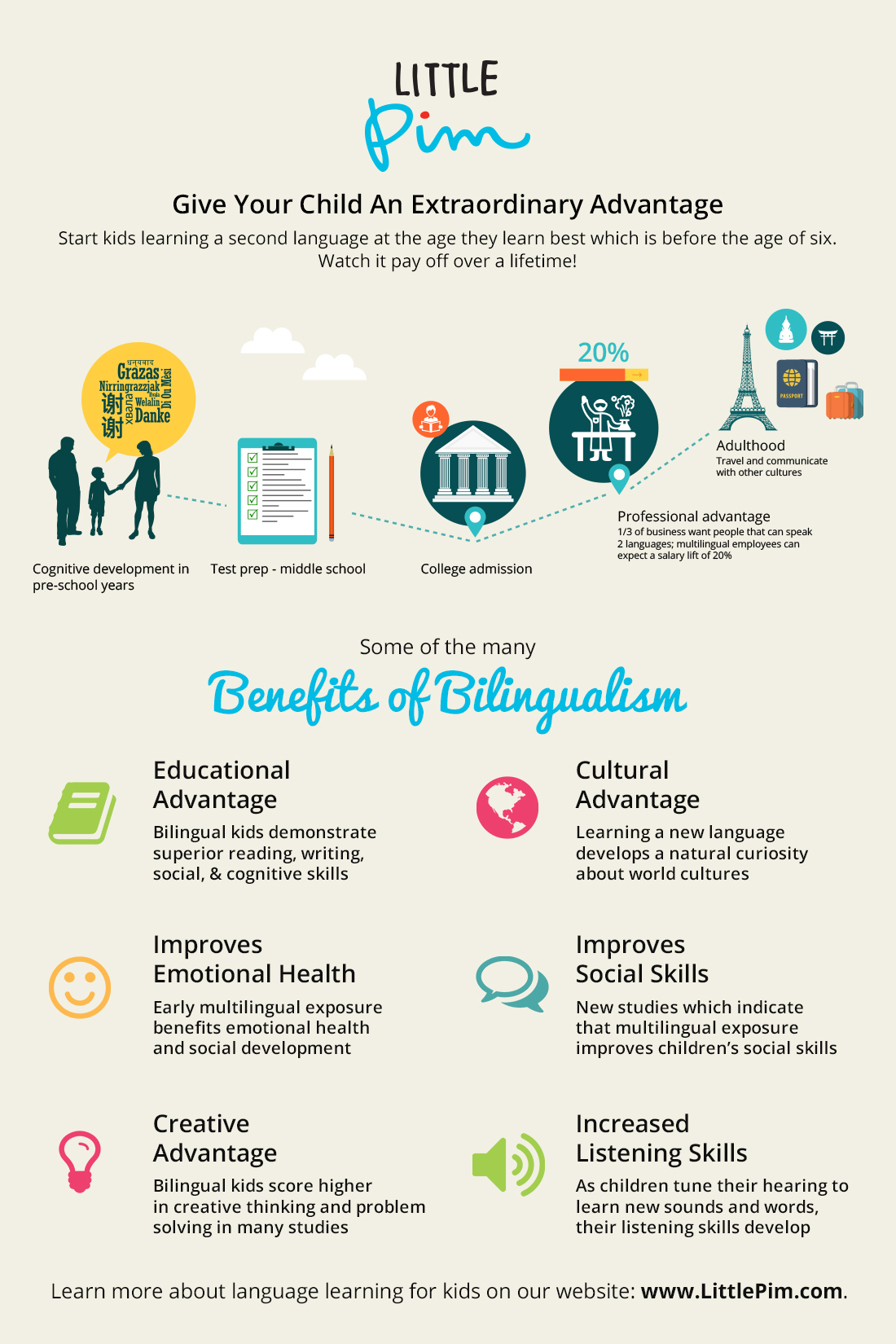

Below is an infographic on some of the many benefits of teaching kids a second language at the age they learn best which is before the age of six. Give a child the gift of a second language and watch it pay off over a lifetime! Share this infographic with parents and teachers and explore more of the benefits of bilingualism on our website.

Bilingual Baby: When is the Best Time to Start?

The benefits of introducing your baby to another language are well documented. In our rapidly globalizing society, knowing a second (or third) language provides an obvious edge over the competition in the job market.

But, what about its impact on childhood development? While some would suggest that over-exposure to foreign language may cause delay in speaking, this assumption is both unproven and outweighed by the benefits dual-language babies experience as they grow.

We know the many benefits, so the question soon becomes: “When do we start?”

The answer is surprising. According to an article by the Intercultural Development Research Association, it may be most beneficial to begin second language exposure before six months of age. In a study by psychologist Janet Werker, infants as young as four months of age successfully discriminated syllables spoken by adults in two different languages. Dr. Werker’s work also determined a possible decline in foreign language acquisition after 10 months of age. To give your child their best start, you must begin early.

How is this so? The answer can be found in the complex world of the human brain. Our brains react uniquely to language learning at any age, even growing when stimulated by another language. While mankind can acquire a language at mostly any stage, it is exceptionally difficult to do so outside of childhood. From infancy to age five, the brain is capable of rapid language acquisition. Even so, there are varying degrees of acquisition, even for children. After six months of age, infants begin distinguishing the differing sounds of their native tongue and others. Beyond six months, exposing your little one to a brand new language will pose a challenge.

That is not to say that teaching your two year-old French is a bad idea! It is merely to say that the earlier you begin teaching your child, the better.

Though most babies wont utter their first words before eleven months of age, they develop complex mental vocabularies through the piecing together of “sound maps.” As they gather from what they are exposed to, an infant who hasn’t been immersed in another language during this delicate stage will not piece together adequate sound maps to differentiate another language.

The reason for this is rooted in the brain at birth. Children are born with 100 billion brain cells and the branching dendrites that connect them. The locations that these cells connect are called synapses; critical components in the development of the human brain. These synapses are thought to “fire” information from one cell to another in certain patterns that lead to information becoming “hardwired” in the brain. The synapses transmit information from the external senses to the brain via these patterns, thus causing the brain to interpret them, develop, and learn from them. From birth to age three, these complex synapses cause infants to develop 700 neural connections per second.

These synapses are critical in sound mapping, and at the age of six months, the infant brain has already begun to “lock in” these new patterns and has difficulty recognizing brand new ones. This is because although your baby is born with all of the neurons they’ll ever need, that doesn’t mean that they’ll “need” all 100 billion. Infancy to the age of three is filled not only with rapid neural expansion, but also with neural “pruning;” a process in which unnecessary connections are nixed and others are strengthened.

Exactly which connections are pruned and which are cultivated is partially influenced by a child’s environment. Synapses are cultivated or pruned in order of importance to ensure the easiest, most successful outcome possible for a functioning human being. If a function is not fostered during this stage, it is likely that the neural connections associated with it will fade. For the brain to see a skill as important, you must make it important.

To put it plainly, if you only speak to your child in English, the infant brain sees no reason to retain a neural pathway regarding the little Mandarin it has heard. Babies learn about their environment at every age and are internally motivated from birth to do so. Your baby wants to learn and does so by exploring and mimicking the world around them. They’re entirely capable of building a complex knowledge of Mandarin, Arabic, or Italian. So, why not feed their mind and start now?

Stanford researchers say early language learning is critical

How do we begin to learn a language? How do young children go from the "goo" (baby talk) to being able to form real words and sentences by the time they're toddlers? In the video below, Stanford researchers discuss their studies involving children's language learning, what abilities are involved in language learning, and how language interacts with kids' understanding of their social world.

[youtube id="TBiE5F83ZE4"]

The researchers explain the importance of understanding how kids learn so that we can begin to design better early childhood intervention programs for kids who aren't getting enough language input, or in cases of developmental disabilities.

They also stress that the language children are exposed to in infancy and early childhood has a huge impact on their later language and academic abilities. As Associate Professor Michael Frank says in the video,

The language exposure you get early on in life is really critical for your later language proficiency and your school performance.

Their conclusion backs up the premise behind our award-winning language learning program: the best time for kids to learn a language is before age 6. Be sure to check out the research behind our method to learn more about how we integrate scientific studies like these to help kids effectively learn languages, both native and foreign.

3 Things You Didn't Know About the Bilingual Brain

The internet is abuzz with news of a new study published in the journal Neurology that indicates that bilingualism can delay the effects of dementia (including Alzheimer's). While other researchers have certainly drawn the same conclusion in the past, this study has the largest sample size and is certainly worth reading about! But if you're more interested in how learning a second language will impact your child's brain NOW, here are a few more fun facts about the bilingual brain and language development from some of our favorite articles around the web:

- Children who learn multiple languages may make grammatical errors at first, but it won't last! Just as monolingual children sometimes make errors as they begin to learn the structure of a language ("I go'ed" vs. "I went"), so do bilingual or multilingual children. It's all a part of the language learning process.

- Socio-economic status has a greater effect on vocabulary than bilingualism. Some parents fear that adding a second language to the mix will stunt their child's development in their first language, but more and more evidence indicates that multilingualism is an insignificant indicator of how a child's vocabulary will develop. Read more at the New York Times.

- On the other hand, speaking a second language helps delay dementia regardless of education level. This new study demonstrates that even illiterate participants reaped the benefits of bilingualism, experiencing the same 5-year delay in symptoms as more formally educated participants.

Little Pim on NBC's Weekend Today Show Segment "Visiones"

Little Pim's founder Julia Pimsleur Levine was on NBC's Weekend Today (WNBC/NY) on Saturday! Click the video below to watch Julia's interview with Lynda Baquero, host of "Visiones".

Julia and Lynda talk about Little Pim and discuss just how easy it is for young children to absorb new languages.

Hear what Julia has to say on bilingual kids, learning a new language and early childhood development, and see just how easy it is for your kids to learn a new language with Little Pim!

The benefits of bilingualism - Dr Bialystok

Here at Little Pim, we’re well versed in the benefits of foreign language learning. We know just how important it is for a child’s early development, the advantages multilinguals have in reading, math and social skills, and how it improves memory overall. Journalist Claudia Dreifus’s excellent interview with Dr. Ellen Bialystok serves as a good reminder of just how critical language learning can be for young minds. Printed in the New York Times Science section this week, Dr. Bialystok’s interview is currently the most emailed article on NYTimes.com, and makes for a truly fascinating read.

Dr. Bialystok is a leading psychology professor, whose main academic focus is bilingualism and its effect on language and cognitive development in children. She has received many prestigious awards for her research, including the Killam Prize and the Pimsleur Award for Foreign Language Education (named for my late father, Dr. Paul Pimsleur).

I’ve highlighted a few of Dr. Bialystok’s main points she made in this week’s New York Times piece:

As we did our research, you could see there was a big difference in the way monolingual and bilingual children processed language. We found that if you gave 5- and 6-year-olds language problems to solve, monolingual and bilingual children knew, pretty much, the same amount of language.

But on one question, there was a difference. We asked all the children if a certain illogical sentence was grammatically correct: “Apples grow on noses.” The monolingual children couldn’t answer. They’d say, “That’s silly” and they’d stall. But the bilingual children would say, in their own words, “It’s silly, but it’s grammatically correct.” The bilinguals, we found, manifested a cognitive system with the ability to attend to important information and ignore the less important.

…There’s a system in your brain, the executive control system. It’s a general manager. Its job is to keep you focused on what is relevant, while ignoring distractions. It’s what makes it possible for you to hold two different things in your mind at one time and switch between them.

If you have two languages and you use them regularly, the way the brain’s networks work is that every time you speak, both languages pop up and the executive control system has to sort through everything and attend to what’s relevant in the moment. Therefore the bilinguals use that system more, and it’s that regular use that makes that system more efficient.

Q. One would think bilingualism might help with multitasking — does it?

A. Yes, multitasking is one of the things the executive control system handles. We wondered, “Are bilinguals better at multitasking?” So we put monolinguals and bilinguals into a driving simulator. Through headphones, we gave them extra tasks to do — as if they were driving and talking on cellphones. We then measured how much worse their driving got. Now, everybody’s driving got worse. But the bilinguals, their driving didn’t drop as much. Because adding on another task while trying to concentrate on a driving problem, that’s what bilingualism gives you — though I wouldn’t advise doing this.

Not convinced yet? There is more!

On average, the bilinguals showed Alzheimer’s symptoms five or six years later than those who spoke only one language.”

You can read the piece in its entirety here:

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/05/31/science/31conversation.html

I also recommend Dr. Bialystok’s “Language Processing in Bilingual Children” if you’re interested in delving into her research, which covers many of her discoveries in more depth:

Little Pim parents are always telling me of the benefits of foreign language learning for their children – benefits that extend beyond the obvious ability to communicate in another language. I’d love to hear your thoughts and observations about how introducing your child to another language has affected their early development. I know that my son had an easier time recognizing “big words” in English because he could recognize the French root in words like “chagrin” (which means sad in French) or “collage” (from the French word colle, which means glue). He is also accustomed to absorbing vocabulary words, which has improved his concentration and ability to stick with challenging mental tasks. What have you seen in your kids?